Revolutions Reveal an Asian Streak in the Russian Soul

RussiaProfile.Org, an online publication providing in-depth analysis of business, politics, current affairs and culture in Russia, has published an unusual Special Report on the mysterious "Russian soul". Fifteen articles by both Russian and foreign contributors examine this concept, which has been used by Russia watchers for some 150 years, from a contemporary perspective. The following article is part of this collection.

The character of the Russian revolutionary is recognizable and universally known, since some of the best-known figures of Russian history were, at least at some stage of their lives, revolutionaries. Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin were professional revolutionaries who chose the career of professional insurgents early in their lives. Alexander Herzen, Pyotr Kropotkin and Mikhail Bakunin, unlike Lenin and Stalin, never came to political power, but the dramatic character of their personalities, as well as the scope and bravery of their political and philosophical thought, fascinated Western thinkers. From Albert Camus to Tom Stoppard, West European playwrights made Russian revolutionaries into the central characters of their plays, centering their research on the two main traits of a Russian revolutionary—the pursuit of mostly utopian designs and the indiscriminate use of moral and (more often) immoral means for the realization of their cherished utopias. This pattern of revolutionary behavior, established in Russia in the middle of the 19th century, proved to be remarkably tenacious and universal. It continues to reveal itself to this day not only in Russia, but also in other parts of the globe, from China to Venezuela.

Annihilation as a principle

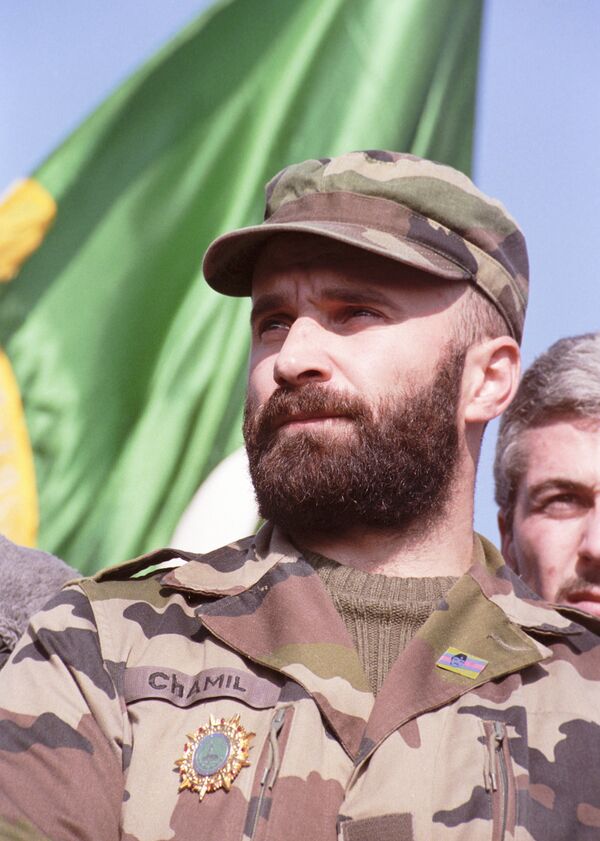

There are two other characters not as well-known as Lenin or Stalin, and many would prefer to see them as common outlaws, not political activists, due to the infamy that rightfully surrounds their names. However, the 19th century revolutionary radical Sergei Nechayev and the recently deceased Chechen separatist Shamil Basayev considered themselves revolutionaries to an even greater degree than Lenin and Stalin. They were so consequential in their pursuit of destruction that to them, even the makers of the Russian Revolution of 1917 were weak-kneed “deviationists.”

Nechayev and Basayev allow for studying the phenomenon of the Russian revolutionary since they both were “pure” revolutionaries, devoting to this passion all their lives and never being satisfied with the amount of destruction they managed to achieve. Nechayev was the perpetrator of one of the cruelest political murders of the 19th century in Russia, and only incidentally failed to commit many more similar crimes. The actual number of victims of Basayev’s terrorist attacks may never be known, since he claimed responsibility for some of the the bloodiest hostage takings in human history—the hospital siege in Budyonnovsk in 1995, the theatre siege on Dubrovka Street in Moscow in 2002, and the school siege in Beslan in 2004.

Anti-Europeans

The fact that Basayev was an ethnic Chechen and claimed to be Muslim does not undermine his standing as a Russian revolutionary in any way, not only because Basayev left his native Chechnya at the age of 17 to spend many years in Moscow and other Russian cities. And not only because he positioned himself as a revolutionary since his first terrorist act in 1991—hijacking a plane to protest attempts by the Russian government to quell unrest in Chechnya. He also explained his most terrible crime—the terrorist raid against Dagestan in 1999—by his desire to “jumpstart” an Islamic revolution in Russia. What puts Basayev in the ranks of Russian revolutionaries is the fact that religious and ethnic minorities were at the vanguard of Russian revolution since at least the middle of the 18th century.

Yemelyan Pugachev, the leader of the biggest Russian peasant rebellion against the Empress Catherine the Great, until his execution in 1775 relied heavily on Muslims and Old Believers. It is interesting to note that Catherine’s ill-wishers in Western Europe laid big hopes on Pugachev’s success, even though the impostor, who claimed to be Catherine’s “husband,” planned to turn his energies against the “decadent” Western Protestants and Catholics upon taking power in St. Petersburg.

The irony of this story will repeat itself on many occasions in the future. Russian revolutionaries, from dissident émigrés Nechayev and Lenin to the “romantic avenger of his people” Basayev, often enjoy sympathy and even direct support in the West, but they inevitably become anti-Western upon coming to power. Basayev started making vitriolic anti-Western speeches and turned a blind eye to the kidnappings of Western journalists soon after becoming independent Chechnya’s “prime minister” in 1996. These were often the same journalists he coddled and protected as Chechnya’s chief public relations spokesperson during the war of 1994 to 1996, inducing them to write bewildering stories about the Russian troops’ behavior.

And this is just one example of many. Upon coming to power in Russia in 1917, Lenin began financing and arming subversive organizations in that same Germany which helped him to return to Petrograd in April of 1917 and viewed him as a useful tool in subverting the tsar’s regime. Stalin, who once became a delegate at the London Convention of the Bolshevist Faction in 1905, profiting from a visa free-regime that existed in Europe at the time and included Russia, upon coming to power shut off Russia from the West by an iron curtain that not even the medieval isolationist Ivan the Terrible could imagine.

The anti-Western character of post-revolutionary regimes proves the intrinsically anti-Western character of Russian revolutions as a social phenomenon. Despite their initially “progressive” rhetoric (usually this rhetoric is directed against the Russian autocracy, which endears the movement to the West), revolutions in Russia tend to be basically reactionary affairs, throwing the country back in its development and isolating it from the rest of Europe. Many historians believe, with reason, that revolutions reveal the Asiatic part of the Russian soul.

The February Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991 were not revolutions in the classical Russian sense, since they were “revolutions from above”—successful conspiracies inside the ruling circles, which used the protest of the impoverished population to dismantle those controls of the old regime that burdened the younger representatives of this regime’s own elite. In “real” revolutions (the so-called “revolutions from below,” where the masses play an active role) the same unfortunate pattern repeats itself. As soon as the hated autocracy weakens its grip on power, the most radical and usually anti-Western elements shake off the “soft-fleshed” liberals inside the movement, imposing a reign of terror first inside their own party and, in case of success, inside the whole country.

Ambitions without prospects

Sergei Nechayev (born in 1847, died in 1882) was a vocal example of the above-described pattern of a Russian revolutionary’s behavior, and this was part of the reason why the famous Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky, himself a former revolutionary, made Nechayev the prototype of one of the characters in his anti-revolutionary novel “The Devils.” Born into a family of modest income, his mother a simple peasant, Nechayev was a talented and ambitious youth, but the existing political order left little room for his ambition. Converted to the most radical revolutionary ideas at the age of 21 to 22, he revealed a great talent for organization and leadership. The fact that at the age of 31, he managed to convert to his revolutionary views even the guards of the top-secret prison in St. Petersburg where he had been forced to spend the last ten years of his rather short life for murder, exemplifies his extraordinary gift of persuasion. Nechayev’s plan to flee the prison with the help of the guards he “proselytized” failed only because of a report by one of the terrified “converts.”

Historians similarly agree on Lenin’s extraordinary talent for persuasion. Like Nechayev, whom the latter commented on positively in his private conversations, Lenin opted for the life of a professional revolutionary at the age of 20. So why do talented people so often become revolutionaries in Russia?

The answer is simple—a lack of opportunities for career development and a prosperous life within the established social structure. “Could people like Nechayev, a church school teacher with an incomplete education, like the assistant provincial attorney Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin’s real name) or like mediocre prose writer Viktor Chernov (the future leader of the Russian party of Socialist Revolutionaries)—could these people hope for a serious career in tsarist Russia?”—asks at the beginning of his book Felix Lourie, Nechayev’s biographer and a historian of the Russian revolution based in St. Petersburg. Lourie’s answer to this question is negative. “They crammed it into their heads that only a revolution of their own could lead them to the heights of power, and they did not agree to anything less. This simple thought nourished their longing for a speedy revolution, enflaming their impatience and intolerance.”

Until the age of 20 Nechayev’s was the life of an average upstart (Nechayev was born in the region of Ivanovo, a province in the center of Russia). At a young age he made visits to Moscow and St. Petersburg in a bid to enter a university. Having failed the exams, he had to work as a teacher of theology at a regular school, eking out a living with private lessons. Lectures at the university, which he attended on a voluntary basis, did not satisfy him, since a university education allowed one to pass only the first two steps in the 14-step high bureaucratic hierarchy established by Peter the Great that would remain unchanged until the revolution of 1917. So instead of becoming a scientist, Nechayev developed a strong hatred for “useless” intellectuals, a hatred which Lenin, 23 years Nechayev’s junior, would partially inherit. In one of his letters Lenin declared the Russian intelligentsia “the dung of the nation,” thus revealing the true depth of his contempt for knowledge that could not be used in revolutionary practice or, heaven forbid, ran against it.

Murder as a bond

In 1868 Nechayev took part in a student revolt and became acquainted with Pyotr Tkachyov, one of the leaders of the revolutionary movement of “narodniki” (“people’s champions”) which advocated a revolution spearheaded by the Russian peasantry and did not shy away from terrorist acts against the representatives of the tsarist regime. In 1869 Nechayev spent a few months in London and in Geneva, where he met the legendary figures of Russian political emigration—“anarchist” Mikhail Bakunin and “free democrat” Alexander Herzen. For many years, if not centuries, to come, the mailing addresses of Russian radical emigration will remain the same—Britain, Switzerland, and France.

However, Nechayev went much further than even the most radical Russian émigrés could envision. In fact, Nechayev took their ideas to their logical conclusion, saying that a revolution justified everything, including the murder of both the oppressors and the oppressed. He summarized his views in “The Catechism of a Revolutionary,” a program statement published in a few copies in a Geneva publishing house, owned by a Polish émigré Ludwig Czernecki, thus also sealing an unholy union of Russian and Polish anti-government extremists. This union would also last for decades, revealing itself, for example, in the murder of the liberal Tsar Alexander II by a pair of Russian and Polish terrorists.

“A revolutionary is a doomed person,” Nechayev’s statement said. “He broke off all connections to the civil order and to the educated world, with its laws, rules of decency, universally accepted conditions and morals. A revolutionary is a merciless enemy of this world, and if a revolutionary continues to live in this world, he is doing so only in a bid to destroy it with greater certainty… A revolutionary knows just one science—the science of destruction… A revolutionary despises public opinion. He holds in contempt and hates the morals of today’s society. For him, only those things which serve the revolution’s final victory. are moral”

Nechayev himself did not live to realize the principles of his “catechism” in full. In 1869, having returned to Russia from Switzerland, he failed in his first implementation of the “revolutionary morals.” In order to tie together members of his small cell of revolutionary students by blood, he organized a group murder of one of the members, Ivan Ivanov. This student’s fault boiled down to his refusal to glue anti-government leaflets in a students’ cafeteria. The aim of the action was to provoke police to take action against students, which, according to Nechayev’s plan, would add to the number of discontented students and thus bring the regime’s end closer. Ivanov refused, inducing Nechayev to get rid of him in the nastiest possible way, so typical of Nechayev and other Russian revolutionaries in the future. Nechayev first slandered Ivanov in the eyes of the group’s members, saying that Ivanov was planning to report them to the police. He then persuaded the group that the only way to avoid arrest was collectively murdering the “renegade.” Ivanov was slaughtered in November of 1869 by Nechayev and four other students in a dark part of the park of the Moscow Agricultural Academy. Nechayev made all those present participate in the murder, but made the final shot to Ivanov’s head himself.

The murderers did a sloppy job of hiding the body, and the murder was quickly solved by the Moscow police. Members of the group were arrested, but Nechayev managed to flee to Switzerland, where the Swiss government refused to extradite him, saying that he had no chance of a fair trial in Russia. In 1872, however, Russian secret police managed to arrange for Nechayev’s arrest in Zurich. Protests by Russian émigrés and other people who would now be called human rights activists followed. Only with great difficulty, foiling several liberation attempts, did the Russian agents manage to transport Nechayev first to Moscow and later to the courtroom, where he was sentenced to 20 years of forced labor. He only managed to serve ten years. A failed escape attempt, which led to the arrest of 34 prison guards and the assassination of Tsar Alexander II by his fellow “narodniki” in 1881, led to Nechayev’s being put under even closer watch than before. “All of his body’s reserves were exhausted,” wrote Lourie. In 1882 Nechayev succumbed to scurvy.

The worse, the better

While appearing different on the surface, Russian revolutionaries are united by the formula “the worse—the better.” Instead of battling injustice they often strive to perpetuate it in order to bring about the collapse of the “reactionary” social order. Nechayev deliberately sent anti-tsarist letters to some of the liberal members of society, knowing that these letters would be read by the police and cause his addressees trouble, thus increasing the number of the revolution’s supporters. In the same way, Basayev in retrospect seems to have been provoking an armed Russian response to his actions, so that the Chechen people would suffer more and become stauncher enemies of the Russian state—and consequently his most loyal supporters.

Basayev’s attack against Dagestan in August of 1999 does not appear to make any sense if one looks at it from the point of view of Chechen national interest. Just recently, in 1996, the Chechen separatists had fought their way to de facto independence from Russia. Why provoke Russia into a new attack, worse still than the one Chechnya had to face in 1994 to 1996? Besides, Dagestan was populated by fellow Muslims, who would be the first to suffer from a Chechen attack. From the standpoint of normal human logic, the attack did not make any sense at all. But from a revolutionary standpoint, it did. The new spiral of violence led to the radicalization of more Chechens and Dagestanis, allowing Basayev to enlist more “soldiers” for his abysmal terrorist acts in Dubrovka and Beslan. A continued peaceful period in Chechnya would have revealed Basayev’s total incompetence as the “prime-minister” of Chechnya, a post he officially occupied under “President” Aslan Maskhadov. Both Basayev and Maskhadov proved to be much better revolutionaries than economic managers—a pattern that was first discovered by Lourie: “The Russian revolutionaries hate slow and steady reforms of the state and economy, because this process leaves no room for them in the administrative hierarchy of the Russian state,” Lourie wrote in his 2004 biography of Nechayev. “Fearing a prepared constitution, the leaders of the ‘People’s Will’ hastened to murder the liberalizing Tsar Alexander II. A Constitution from the tsar’s hand would certainly have led to a decrease in revolutionary activity. In the same way, Lenin hastened with his coup in the Winter Palace in 1917, before the convention of the Constituent Assembly could take place a few weeks later.The improvement in the people’s condition inspired fear in the revolutionaries because it could leave them unemployed.”

This pattern of behavior explains the actions of many modern Russian revolutionaries, from Basayev to punk writer Eduard Limonov. To provoke the state into a violent response and feel needed again—such is the tactic that rarely fails them. It also never fails to bring them new supporters among exalted Western journalists. But there was one thing that Russian revolutionaries never achieved—making people happy. Happiness is incompatible with the Russian revolution; for Russian revolutionaries, happiness too is a bourgeois feeling.

By Dmitry Babich

Russia Profile