The events that took place in the Baltics in January 1991 turned the tide on the Soviet Union's history. They showed that the allegedly "destructive forces" driving the confrontation had both sufficient will and a clear understanding of their goals, while the advocates of "law and order" had neither.

As a result, political elites in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia achieved all the goals they formulated so clearly 20 years ago (whether or not this has made their people happy is another matter), whereas the Russian elite, as the legal successor to the Soviet nomenklatura, is still going in circles for lack of a strategy.

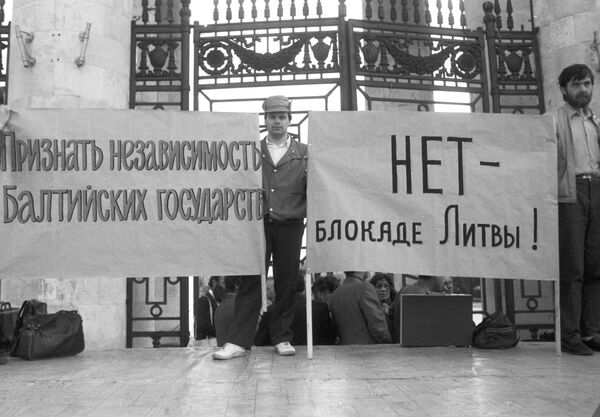

Twenty years ago there was a palpable sense of outrage among a large section of Soviet society. In part because the federal authorities were using military force to suppress people's striving for freedom, but also because the Kremlin was so inept and inconsistent in that endeavor. This sense of loathing only grew when Moscow tried to shift the blame for the failed attempt at reinstating Soviet power in Lithuania and Latvia onto local forces.

History is written by the winners, and history books will tell the story as presented by the Baltic countries: they got what they wanted. For them, January 1991 is part of the national myth that is vital for any stable state. Although disputes remain, as shown by the Twenty Years After the USSR project, the fundamental view of those events is unlikely to change.

Liberation from the totalitarian Soviet monster will remain both the starting point and chief source of legitimacy for people across Central and Eastern Europe, at least until they detect some other threat to their sovereignty. Other interpretations, raising the specter of external forces, deliberate provocation, personal ambition and politicking freedom fighters, will remain marginal.

Twenty years after 1991, Russia still has not settled on a view of those events. Taking its first steps as a democracy, it attempted to join the ranks of other "young democracies" and embrace the ideology espoused by national democrats across the former Soviet republics and Eastern Europe. But it soon became clear that this was an impossible goal to achieve, because these countries see Russia as their departure point and the West as their destination. They were desperate to return to the bosom of Europe, whence they were so cruelly snatched in the 20th century by the Kremlin's evil genius.

Russia ? diminished and dilapidated after the Soviet Union collapsed ? could not escape from itself. It remained a great power with the mentality and history to match, not to mention responsibility for a vast territory across Eurasia.

Moscow could not disregard its Eurasian neighbors, if only because uncontrolled post-Soviet disintegration would have boomeranged right back at it. In fact, the positive role Russia played in Eurasia in the 1990s has yet to be properly assessed and appreciated.

Likewise, the Kremlin could have buried communism by declaring that it is not responsible for the Soviet regime's crimes, especially in the Baltics. Moreover, it could have claimed the prize for the fact that Russia, led by Boris Yeltsin, made what was perhaps the decisive contribution to the final dissolution of the Soviet empire.

But the people were not ready then, and they don't seem to be ready now. In the absence of other ideals the Soviet Stalinist myth proved extremely viable. On top of that, Russia could not refuse to accept its status as the Soviet Union's legal successor: doing so would have deprived it of the many important international instruments it inherited.

This created a kind of conceptual uncertainty. Russia has not yet found a new national idea. Regaining its former status and boundaries was likewise impossible: Russia was in disarray and spent a long time trying to preserve its territory at least within the new post-Soviet borders. No one wanted to claim the glory of dissolving the Soviet Union, not even President Yeltsin who seemed to regret he was one of those who had started the process.

As a result, to date Russian society does not know what the Russian Federation is: a full-fledged state, born in 1991 but with a thousand-year history, with all its ups and downs, or a fragment of the "real" homeland that fell apart 20 years ago, that has no future in its present form?

Russia's relations with the former Soviet republics will depend on the answer, when and if we manage to formulate it.

The views expressed in this article are the author's and do not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.