Recently I was browsing in a used book store when I stumbled upon a soldier’s Japanese phrasebook from World War II. Between faded orange covers I found a treasure trove of fascinating words and phrases- certainly it’s the most useful text published by the U.S. War Department I’ve encountered since that pamphlet on sexual hygiene for GIs I found in a Texas ghost town a few years back. It does lack for detailed diagrams of human genitalia, however.

Like most phrasebooks it contains all the standard terminology related to greetings, asking for directions and finding lodgings, but the structure and at least half of the language is strictly determined by the context of war. Thus it begins not with “Hello” and “My name is…” but rather a set of “Emergency Expressions” the very first of which is:

Help! ta-SKET-ay!

Now that is definitely useful, so long as you are talking to friendly Koreans or “Formosans” and not a platoon of Japanese soldiers. Other handy emergency expressions include:

Where are American soldiers? Ah- may-ree-ka no hay-ee-TA-ee wa DOAK-o-nee ee-MA-ska?

Are they our enemies? KA-ray-ra wa tek-ee DESS-ka?

And:

Don’t shoot! OO-tsoo-na!

Only once this type of thing is out of the way does the War Department get down to teaching the basics of polite conversation such as:

Good morning o-ha- YO

And

Will you have a cigarette? Ta-ba-ko o DOAZ-o?

Frequently the phrasebook offers both polite and imperative forms for the same expression. According to the foreword you should be respectful when addressing prisoners in the officer class, but bark at their underlings- that’s the Japanese way, apparently. Thus, when interrogating gentlemen of breeding you say this:

Please tell the truth hoant-o no ko-TOE o eet-TAY KOO-DA-sa-EE

But when it comes to enlisted men, you say this:

Tell the truth! Hoant-o no ko-TOE o ee-YAY!

Perhaps unsurprisingly, no polite form is supplied for the following:

Obey or I’ll fire! Kee-ka NA-eet-o OO-tsoo-zo!

Of course, there are long lists of vocabulary dedicated to rank, terrain and military hardware. A lot of the combat stuff would not be very useful today however…unless you are attacked by a rogue member of the apocalyptic Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo:

I was gassed doak-oo-GA-soo nee ya-RA-ret-ah

I was surprised to find that Section 3 was filled with detailed terminology related to fine dining:

I want it- - koo-da-SA-ee

Cooked or boiled nee-TAY

Raw NA-ma-day

Rare na-MA ya-kee-nee SHTAY

Well done YO-koo YA-ee-tay

Baked or fried YA-ee-tay

Fried in deep fat ah-GET-ay

Roasted RO-sto shtay

War is hell but evidently that doesn’t stop you from squeezing in a good meal whenever you can.

Next come “health” words, which for seriously wounded soldiers would surely have meant the difference between life and death, e.g.:

I am hurt in the crotch/privates ma-TA ga ee-TA-ee

Stop the bleeding shook-KETS o-toe-MAY-yo

Quick! HA-ya-koo!

In conclusion, I’d say that the U.S. War Department did an excellent job of putting together this little phrasebook. The only thing that’s missing is a section dedicated to prostitution, which would have been very useful for some of the GIs, I’m sure. Oh yes, and also: “Where did all these severed heads come from?” an essential phrase for any English speaker en route to Nanking while it was under Japanese occupation in 1937. But then again, America wasn’t in the war yet. Heck, there wasn’t even a war on!

As evocative of a soldier’s reality as any memoir or novel, the War Department’s Japanese phrasebook made me thankful I was born in a different time, and did not have to face death in a hostile jungle. Which reminds me: my well-thumbed copy came to me with the previous owner’s name still penciled on the cover: Captain Pilch. Thus as I flick through its well-thumbed pages (the Captain clearly saw a lot of combat) I draw even closer to that moment in history and ask myself: Did the captain survive? Which phrases did he use the most? Could the Japanese understand him? There’s no way to know. But I am grateful to the Captain for his notations, such as REI for zero which the War Department omitted even though Eastern mathematicians were using it in their calculations long before the turn of the first millennium.

Who knows, perhaps this book even saved Captain Pilch’s life! And just on the off chance that he is still knocking around, aged 95 or so, I have a request to make. On the front cover the phrasebook is marked RESTRICTED. The first page elaborates that “… restricted material may be given to any person known to be in service of the United States and to persons of undoubted loyalty and discretion who are cooperating in government work…” But otherwise that’s it.

Now I’ll admit that since anybody could have constructed this phrasebook out of a big enough dictionary, I don’t quite understand why the War Department felt the need to keep its contents confidential. But I shall defer to their wisdom. So don’t tell anyone I told you all this stuff, OK? For Captain Pilch’s sake (and mine, I suppose).

Unless you happen to know for certain that the RESTRICTED classification has been lifted. In which case tell anyone you like.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and may not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

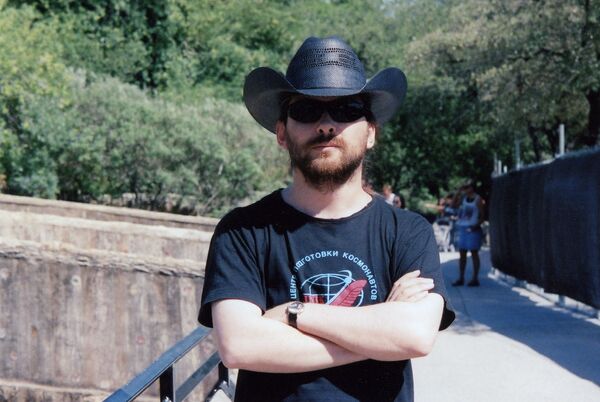

What does the world look like to a man stranded deep in the heart of Texas? Each week, Austin- based author Daniel Kalder writes about America, Russia and beyond from his position as an outsider inside the woefully - and willfully - misunderstood state he calls “the third cultural and economic center of the USA.”

Daniel Kalder is a Scotsman who lived in Russia for a decade before moving to Texas in 2006. He is the author of two books, Lost Cosmonaut (2006) and Strange Telescopes (2008), and writes for numerous publications including The Guardian, The Observer, The Times of London and The Spectator.

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Scotland’s Bid for Independence Explained!

Transmissions from a Lone Star: The art of naming

Transmissions from a Lone Star: My New Year’s resolution – Become more like Lenin

Transmission from a lone star: 2011 - The Year in Dictators

Transmission from a lone star: What I don’t want for Christmas

Transmission from a lone star: Wind of Change

Transmission from a lone star: Cloning the mammoth

Transmission from a lone star: Attack of the Little Satan